A New Model for Economic Specialization

Friday, June 1, 2018

It all started with a question

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about one entrepreneur's failed attempt at specialization. Although she made a strategic misstep in her approach, the general consensus in the business world is that specialization is key to building highly-successful enterprises. Once specialized, firms can earn higher profits, reduce competition, and expend fewer resources to reach their goals.

Why are so many specialists failing?

I often turn to the biological sciences to understand business problems. We all know that many species are going extinct on a daily basis, but did you know that a large number of them are specialists? This fact should call into question the view that niching down is a universal cure to every business ailment. These lifeforms are perishing even though they had seemingly done everything right by specializing: they had adapted their bodies to the types of food they ate, changed their behavior to suit the habitats they lived in, and fine-tuned the ways in which they interacted with other organisms.

If specialization provides a great advantage in the business world, why does it seem so ineffective in the natural world? Why do generalists like cockroaches thrive while specialists like the giant panda are threatened with extinction?

For a while, I found myself unable to come up with a solution to this puzzle. Was there a secondary factor that needed to be considered when specializing?

The answer to my question was a resounding yes.

A burst of insight into specialization

I soon realized that specialization only proves worthwhile when it takes advantage of some aspect of the surrounding environment. For instance, penguins found advantage in specializing in swimming (rather than flying) because they were surrounded by a plentiful supply of fish in the water. Similarly, termites found advantage in specializing in the consumption of wood because there were a great many trees where they lived.

However, many other organisms have been limited because of their specializations. For instance, the rhinoceros stomach bot fly faces a bleak future due to its specialization. The insect has adapted itself to the extreme in order to use the mighty rhinoceros as a host for its eggs. As the number of rhinos dwindle, the fly finds itself a victim of its adaptations and an unwilling participant in a potential coextinction event.

The four quadrants of the specialization model

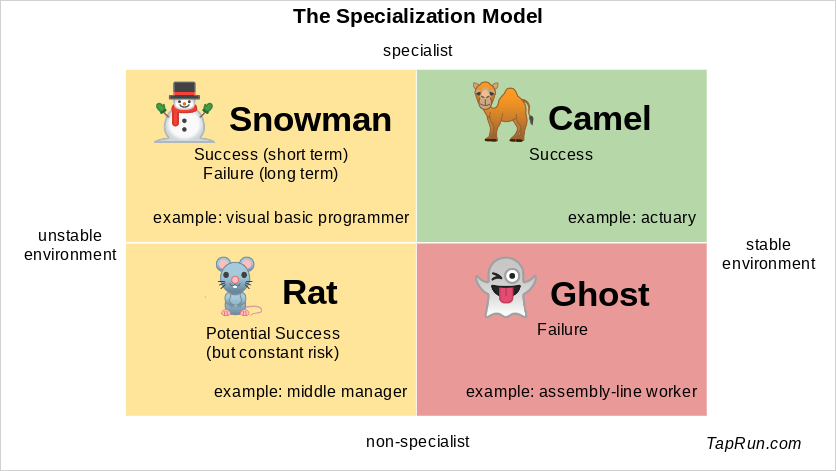

Certain that I was on the right track, I plotted two variables on a grid:

- The degree of effective specialization that has been undertaken (in terms of knowledge, skills, and abilities)

- The stability of environmental factors that allows for benefits to be captured via the specialization

The quadrants, and their representatives, are as follows:

- Camels (specialists in stable environments) - Camels enjoy the greatest chance for long-term success. Participants in this quadrant are able (and willing) to pay the fixed costs required for specialization. In return, players are able to extract the greatest benefit from their environments. Additionally, the adaptations serve as strong barriers to entry for new competitors who might be able to survive on their own but simply cannot compete with specialists who have already adapted to their environments. Because the world around them is stable, the upfront costs are more than made up for by long-term gains.

- Snowmen (specialists in unstable environments) - Snowmen often appear to be camels to the untrained eye. Until the environment changes, they appear quite successful. It is only then that their long-term prognosis becomes clear. Just as snowmen melt when winter turns to summer, some corporations die when interest rates move up, new laws are written, consumer preferences change, or new innovations are introduced. This is not to say that fortunes cannot be made in this quadrant. However, snowmen exist on borrowed time, and the very adaptations that allow them to succeed in the short term may prove useless (or even harmful) from the standpoint of long-term success. The players in this quadrant who fare best are often those that engage in pump and dump techniques to sell their wares and those who are able to accurately predict changes to their environments and either evolve or exit from their ecosystems in short order.

- Rats (generalists in unstable environments) - Rats can enjoy great success under a wide variety of conditions. Their benefit is the same as their curse: they are jacks of all trades, but masters of none. As long as their environments are under constant flux, they are able to thrive. Should their environments stabilize for a time, rats may find themselves unable to compete with those that have undergone specialization. They may also be exposed to great risk during periods in which specialists from elsewhere cross over from similar environments. As such, the ability to weather bad times is crucial for their long-term success.

- Ghosts (generalists in stable environments) - Ghosts are all dead in the long run. They may be limping along, but the world is out to get them. Lacking significant specialization, they have no advantages in their sectors and are unable to present barriers to entry. In the world of business, roles for ghosts will be poorly paid in the short term and automated away in the long term. Those in this quadrant would do well to remember the tale of John Henry. Even the strongest ghosts cannot halt the inevitable march of progress.

A bit of fine print

Although the diagram above uses four distinct quadrants to increase readability, it should be noted that the two axes exist as spectrums. Some members of a quadrant may be more specialized or find themselves in more stable environments than others.

Additionally, the position of a participant within the framework need not be permanent. Members may invest in (or divest from) specialization or find that the natures of their environments have changed. As such, a given entity may find (or intentionally shift) its placement within a given quadrant - or into a different one entirely.

Conclusion

It's true that specialization can be a powerful technique for achieving success. That said, it would be both dangerous and foolhardy to consider specialization to be a panacea for every business problem. A strong understanding of the environment in which one operates is necessary when determining if a given specialization will lead to oodles of profit or a relegation to the dustbin of history.