I Cannot Bear "What the Market Will Bear"

Tuesday, May 15, 2018

I recently walked out of a presentation. I tried to be respectful, but the speaker kept using a phrase that just wasn't appropriate for polite conversation.

The offending phrase? It was what the market will bear.

Do yourself a favor and remove this nasty idiom from your lexicon and make certain to excuse yourself from the presence of anyone who thinks it proper to use it.

Let me ask you this:

- Will the market bear a $1,000 price for a single serving of ice cream?

- Will the market bear a price of $8,000,000 for a single pen?

- Will the market bear a $55,000,000 price for a single watch?

You answer to all three would likely be a resounding "no." Most people would never even think of spending such vast sums of money for some ice cream, a pen, or even a watch.

Of course, what most people do is irrelevant. There are many shoppers for whom money is literally no object.

- There have been plenty of buyers of the $1,000 sundae at Serendipity 3 in New York.

- Anyone with an extra $8,000,000 lying around can enjoy the same pleasures as previous buyers of the Fulgor Nocturnus pen.

- Shoppers willing to part with $55,000,000 can become one of the select few to own a Graff Diamonds Hallucination watch.

Asking what the market will bear is for conventional thinkers who fixate on conventional, mass-market pricing strategies.

The market doesn't actually bear anything. In fact, I would argue that the market doesn't exist at all. Like the invisible hand, it's just a convenient shorthand for economists. The hand doesn't exist and neither does the market.

In many cases, when people say that the market will only bear so much, we should ask ourselves why the price cannot be raised higher. While vendors focused on what the market will bear will be stuck selling products at relatively low prices, unconventional thinkers will find themselves in blue oceans where they can charge much higher prices.

What people call the "marketplace" is really just a collection of shoppers. Each potential buyer possesses a different set of desires, spending habits, needs, and resources. A wealthy person dying of thirst might spend a fortune for a single glass of lemonade. A pauper who just finished a Big Gulp from the local 7-Eleven on the other hand? Not so much.

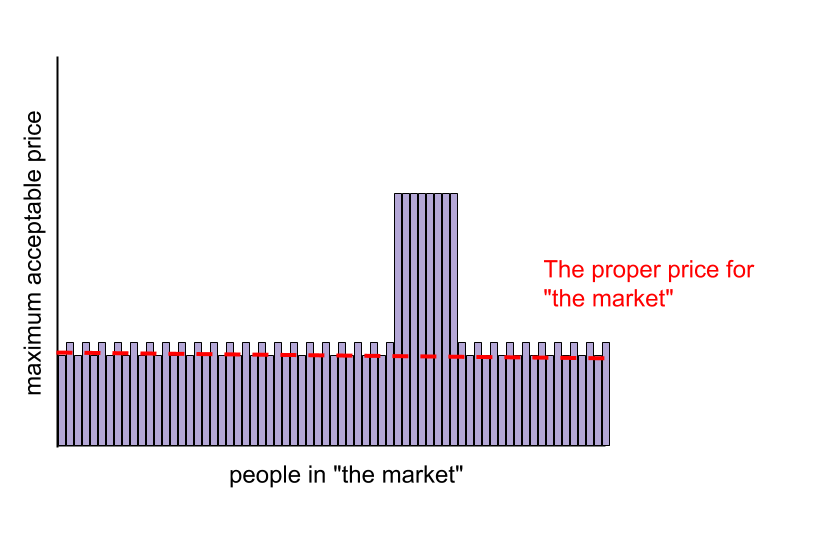

If we were to line up everyone and ask each how much he would pay for an item, we might come up with a chart something like this:

As shown in the chart, some buyers are willing to pay significantly more than others.

Asking what the market will bear is akin to asking what the majority of potential buyers would be willing to spend. But why should a company care about the majority, when it could just target its most profitable buyers?

It might make a whole lot more sense to ask what the most desirable part of the market will bear.

Companies like Apple have long since figured out that addressing the needs of a small segment of the market (the most valuable customers) can prove immensely profitable. Although such vendors may own very small slices of the market, the segments that they service are the most lucrative by far. Sure, cheapskates like me would be unwilling to pay high prices for the vendors' wares, but ideal customers are willing to spend whatever it takes to complete a purchase.

The strategy of focusing on small segments, rather than on entire markets, is one that most businesses would do well to internalize. The old and outdated technique of charging what the market will bear is simply not worth the effort in many cases.

Not only does segmentation allow firms to target their products' specifications directly to the preferences of their ideal buyers, but it allows them to charge a premium for their troubles as well.

So marketers, I implore you: stop asking what the market will bear. Instead, focus on what your ideal customers are willing (and able) to pay. If your goal is to maximize profits, trying to satisfy an entire market will almost always be a losing proposition.