The van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter Is Useless

Thursday, November 1, 2018

I recently listened to a consultant speak about Peter van Westendorp's price sensitivity meter. Although the presenter listed all sorts of facts about it, he missed the most important one of all: the van Westendorp price sensitivity meter is so unreliable that it will prove deadly to just about any businesses foolish enough to rely upon it.

Wait, You Haven't Heard of the van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter?

Don't fret if you haven't heard of it before. Despite its difficult to spell name, its underlying principles are actually pretty simple. At its heart, the price sensitivity meter is just a graph depicting how people feel about a given product at different price points.

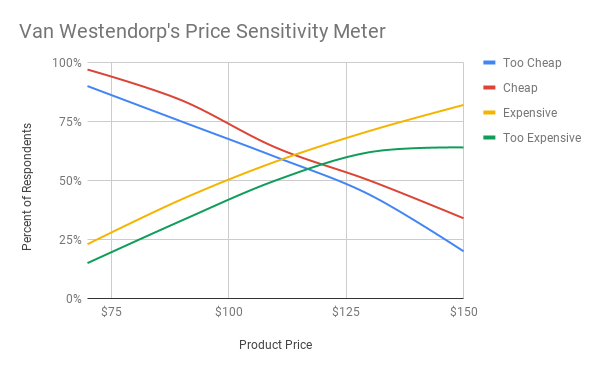

Here's a picture of one that I created:

How to Make a van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter

- Select a product.

- Assemble a team of interview subjects.

- Ask each respondent four questions about the product:

- At what price would the product be too expensive?

- At what price would the product be expensive?

- At what price would the product be cheap?

- At what price would the product be too cheap?

- Plot the responses in a chart with four lines, each representing the responses to one of the questions.

- Identify the locations at which lines cross and note their respective price points. The exact meanings of these points are not standardized, but here are some common interpretations:

- The upper price bound for the product is often given by the location at which the "too expensive" and "cheap" lines cross.

- The optimal price is often given by the location at which the "too cheap" and "too expensive" lines cross.

- The lower price bound is often given by the location at which the "too cheap" and "expensive" lines cross.

Van Westendorp's method has a lot going for it:

- It is easy to implement.

- It results in useful-looking graphs.

- It involves interaction with potential buyers.

- It is widely recognized by experts in the field of pricing.

Of course, the system suffers one serious limitation as well: it provides untrustworthy results.

What's Wrong with the van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter?

With all due respect to Mr. van Westendorp, his creation is a product of its age (1976). Hard sciences like physics study a world operating under rules that do not change over time. Whether one looks to the theories of heliocentrism (1543), gravity (1687), or general relativity (1915), the assumptions upon which they were based are still considered valid.

Economists live in much more dynamic worlds - yet another reason why economists are superior to physicists. Economists are forced to study a world in which participants evolve their behavior, and marketplaces operate under changing rules, expectations, and norms.

Even taken in the best light, van Westendorp's approach features a number of glaring omissions and questionable assumptions - far more than I could possibly describe in a single blog post. Nevertheless, let's take a look at some of the major problems:

It Ignores Competitors

Today's economy is far more competitive than it was in the past. Businesses no longer have the luxury of only worrying about the biggest players. Now upstarts from across the globe can progress from ideation to production in a matter of weeks, days, or even hours. There is little reason to believe that interviewees would have any particular insight into the potential for competition or the strategic barriers to entry that protects a given firm from it.

Even if one assumes that the product in question is superior to that of any competitor (current or future), there is no weight given to the product's discoverability, an important component of pricing power and the "D" in my DUMB model of pricing power. If customers can't find the item, the price being charged is absolutely meaningless, and efforts to optimize it are a waste of precious corporate resources.

It Ignores Strategic Goals

Users of the van Westendorp approach often fall into the common trap of believing that there is one "correct" price.

There isn't.

There is, however, an optimal price for a given goal.

- Is the product intended to saturate a market?

- Is the product intended to penetrate a market?

- Is the product intended to maximize income?

- Is the product intended to boost sales of a complementary good?

Apple has demonstrated quite handily that a business does not have to appeal to the pricing preferences of the masses in order to generate untold profits.

In some cases, high pricing will increase the desirability of an item for a select subset of the population - premium goods and Veblen goods being but two examples.

It Ignores the Effects of Urgency

Would you spend $100 for a glass of tap water?

What if you were in the middle of the desert and dying of thirst?

This is a ridiculous example, I know, but the valuation given by someone in the abstract is often quite a bit lower than what he is willing to pay when a sufficient need arises. Buyer urgency (one of the four components of the DUMB pricing model) can greatly alter a participant's willingness to spend his money for a given product.

There are many offerings, from pain relievers to drain cleaners, that seem to mystically rise in value when buyers discover that they really need them.

It Ignores the Effects of the Sales Channel

Ever since McCarthy developed his concept of the 4 Ps in 1960, marketers have believed that a consumer's perception of an offering will be heavily influenced by the place in which it is sold.

The price sensitivity model completely ignores the product's distribution channel, requiring interviewees to attempt to provide a price without understanding the context in which the product is sold.

The exact same sandwich might command very different prices in various restaurants or parts of the country. This price differential is a reflection of the fact that many products cannot be valued in isolation from their sales channels.

It Ignores the Effects of Marketing

Companies spend billions of dollars on marketing each year. They don't do this because they enjoy spending money. They do it because marketing helps them shape public opinion. Although a person, in the abstract, may set a particular price for a given item, a hearty supply of commercials and a bit of social media influence just might change the way he evaluates the item's worth.

It wasn't long ago that the masses actively derided the very idea of paying for bottled water. Now millions of Americans buy bottled water without giving the matter a second thought.

It Ignores Seasonality

As they say, "to all things there is a season." In many cases, the pricing power of a given item will be highly dependent upon the time at which it is offered for sale.

- People will spend more for a winter coat in late fall than they will in early summer.

- People will spend more for sailing lessons in summer than they will in the winter.

- People will spend more for tours of apple orchards in autumn than they will in winter.

While demand for some products are tied to the season, others follow a different chronology.

- Items with network effects (such as the telephone) offer relatively little in terms of pricing power at their introduction but prove significantly more valuable as their popularity increases.

- Items that are associated with an external movement or personality (such as a politician or an athlete) may offer pricing power that rises and falls with that to which they are connected.

- Items that push the limits of technological sophistication (such as a specific laptop model) may lose pricing power rapidly as further innovations are made and more powerful models are introduced.

It Ignores the Power of Pricing Trickery

More and more often, a product's apparent cost is not the same as its actual cost.

Between upcharges like shipping and handling, upsells, charm pricing, bundlespricing, decoy pricing, and a hundred other pricing ploys, the true cost of a product is not entirely obvious to buyers at time of purchase. As a result, a survey asking what a group is willing to pay may not be entirely relevant.

It Ignores the Value of Vendor Support

Many buyers are willing to spend more money when they feel more confident that the product is reliable. Warranties, guarantees and promises of satisfaction will often boost a product's pricing power, yet cost the vendor relatively little. Asking interviewees to focus upon a product in isolation of secondary sources of value will often lead to lower price recommendations.

It Ignores the Effects of Familiarity

As a buyer becomes more accustomed to, and familiar with, a given item, his opinions of a product's value will often either increase or decrease. A buyer's initial impression may provide a vastly different valuation than his opinion after his experience with the good has increased.

The delta between initial and experienced valuations may lead early buyers to become vocal with their opinions and to attempt to affect the valuations made by potential buyers. For items that are purchased on a routine basis, the delta will also affect the buyer's own propensity to pay as well.

It Lacks Standardization in Methodology

The use of the Van Westendorp approach appears to be haphazardly implemented by analysts and researchers. This may lead to situations in which results cannot be replicated consistently.

- Researchers rarely make use of a control group. It would not be difficult to ask buyers about their views on well-understood product lines in order to determine the validity of their viewpoints.

- The questions are often posed differently by each researcher. Some interviewers even go as far as to predetermine the price points which respondents may select. Such approaches have the potential to taint the responses of interviewees through anchoring.

- The means by which the resulting chart is interpreted is not formalized. Some analysts attribute different meanings to different points of intersection.

Conclusion

If you hear someone utter the term "van Westendorp Pricing Sensitivity Model" without snickering, do yourself a favor and run for the hills. While the model may sound impressive and even look impressive, it really isn't.

It's little more than quackery of the first order. Anyone foolish enough to rely upon it will not be able to help you improve your pricing strategy.

Fortunately, I'm available to point you in the right direction.