Pricing a Depreciating Asset

January 2021

Hello Pricers,

Many people conflate the winter season with the concept of gift giving. Indeed, roughly a trillion dollars are spent on presents each year.

I am not immune to this effect. For the first time in more than three years, I'm including an unexpected gift in this very newsletter: a graph.

I added a graph because it helps to explain the answer to this month's question. Many businesses go out of their way to add a little something extra without asking themselves if it boosts the value that their customers receive.

Does your business invest its time, attention, and resources to provide features, promises, or price concessions that your customers don't care about?

Why?

Pricing Question from a Reader

I sell assets that lose value over time, and I can't seem to find any information about how I should price them. Is there some kind of different way I should approach their sale compared to the way people sell "normal" goods?

Depreciation is a topic that is frequently discussed - I even wrote a guide to depreciation myself. Unfortunately, most examinations of depreciation are focused entirely upon the minimization of tax burdens. They provide little insight as to how such products should be marketed and sold.

Vendors would be well served to consider the effects of depreciation on their offerings' pricing power when considering their pricing strategy.

Start with price skimming

Many firms have found great success in applying the price skimming tactic to the sale of depreciating goods. Using this method, firms tie the prices of their goods to their offerings' value. As an item's value drops, so does its price. Assuming sufficiently large reductions in price, this method allows firms to attract customers throughout their offerings' life cycles.

Unfortunately, there are two major limitations to this approach:

- It provides minimal insight into the means by which depreciation occurs

- It presumes that depreciation, and customer perception thereof, cannot be actively managed by vendors

Causes of depreciation

Before we can present a more complex model for pricing depreciating assets, it is important to survey the major causes of depreciation:

- Usage - Many products maintain a relatively stable value while being stored but wear out as they are used. For example, a pencil manufactured ten years ago will maintain the vast majority of its value while unused but will rapidly drop in value as customers engage its functionality.

- Age - Other products lose value even as they await their initial sale. Many chemicals, such as bleach, will begin to lose potency as soon as they are manufactured.

- Customer preferences - Some products undergo a severe reduction in desirability even when their characteristics remain unchanged. A mint condition beanie baby, for instance, that was once worth a small fortune would now command a significantly lower price.

- Competition - As product categories mature, existing offerings often face downward pressure on prices from more desirable offerings. Early word processing applications lacked desirable features such as spell checking, footnoting, and graphing capabilities. While state of the art at the time, ancient word processes are now seen as functionally deficient and wholly undesirable when compared with modern systems. It should be noted that increased competition need not come from superior alternatives. Vendors of commodities will often experience a significant drop in pricing power when additional supplies or suppliers enter the market.

Stages of depreciation

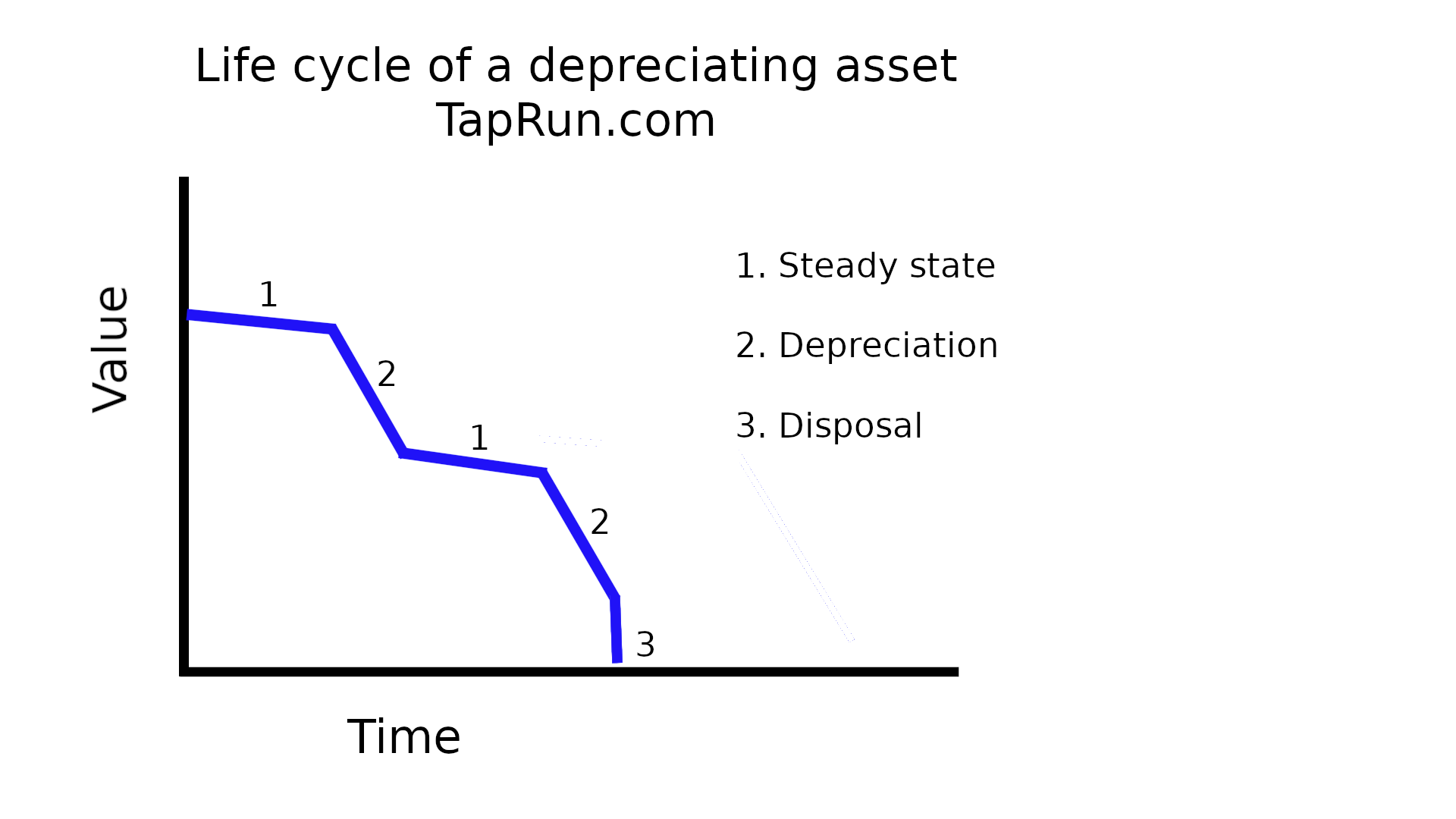

A depreciating good's life cycle can be understood in terms of a stepped graph, as shown below. It should be noted that the stages are not drawn to scale. Depending upon the particulars of the product in question, its customer base, and its market, each stage can vary greatly in length.

- Steady state - For a period of time the item will maintain a relatively stable value. In this state, the perceived value among buyers is relatively constant either because reductions in value are minimal, or they are not being signaled in a manner that buyers can detect and interpret properly.

- Rapid depreciation - After an inflection point, the value of the item will begin to drop quickly. This point often represents the time at which an item's true value is more accurately signaled and more difficult for vendors to obscure.

- Repetition of the first two states - Depending upon the nature of the offering, the offering may find a new use, customer base, or value proposition at which its price will become relatively stable and additional reductions in value become more difficult for buyers to detect. Although the chart depicts a single repetition, the number of cycles can vary greatly. Durable goods may face many cycles of depreciation, while others may experience very few, or even none at all.

- Disposal - As depreciation takes its toll, there will come a point at which the product's value has dropped so much that it no longer attracts any meaningful interest from potential buyers. Although some might imagine that this point occurs when a product's value approximates zero, it can occur far earlier, as dictated by customer search costs and vendor holding costs.

Tactics for minimizing the effects of depreciation

Based upon the graph above, it should be clear that vendors will almost certainly find it advantageous to sell their wares as early in a product's life cycle as possible. What may not be as obvious is that vendors can often take action to slow the effects of deprecation upon their wares. This can be accomplished by the following three methods:

- Increasing the relative length of each stage

- Reducing the magnitude of depreciation in each stage

- Increasing the time before disposal becomes necessary

Increasing the relative length of each stage

Firms will likely find the most success in increasing the length of each stage by pursuing one or more of the following strategies:

- Re-engineering the offering - Improved quality and design can allow products to more readily maintain their value.

- Performing preventive or corrective actions - Firms can implement regular servicing and additional environmental constraints.

- Selling products earlier - Pre-selling or even a focus on selling products earlier will effectively lengthen the early stages of the product's life cycle.

- Reducing production batch sizes - The fewer items in inventory at one time, the less time-based depreciation each will incur prior to sale.

- Utilizing messaging to change perceptions - Clever marketers may be able to push buyers' perceptions of inflection points further out at relatively little cost to the vendor.

Reducing the magnitude of depreciation

- Re-engineering the offering - Improved quality and design can reduce the magnitude of depreciation at each stage.

- Reducing the proximity between devalued and non-devalued items - Buyers who are allowed to created a mental link between undepreciated goods and their future depreciated states will be more conscious of the fact that their purchases will depreciate.

- Obscuring the signals of depreciation - In many cases, signals of depreciation can be hidden or eliminated. For instance, many morally flexible fish shop owners are known to remove the eyes of their fish prior to sale. This is because cloudiness in the eyes is a dead giveaway as to a fish's lack of freshness.

- Confusing buyers as to the meaning of signals - Some vendors attempt to convince buyers that signals of depreciation are actually signals of appreciation. For example, many people have been conditioned to believe that all wines improve their flavor over time. In fact, age only improves some types of wine, while it causes others to turn into vinegar.

- Offering warranties and service contracts - Promises to repair and support items will not only reduce the perception that an item's value will drop over time, but imply a high level of quality for the item's current state.

Increasing time before disposal

Two of the most common means of delaying disposal phases are as follows:

- Re-engineering the offering - The use of higher quality and more sturdy components may extend the lifespan of a product significantly.

- Finding new uses for the offering - Many products that reach end of life for a particular usage may still be useful for other purposes. For instance, Wendy's is known for using unsold hamburgers as ingredients in its chili.

- Increasing customers' ability to upgrade and repair the offering - Changes to the product, its documentation, and the availability of its components can allow users to maintain their products for longer periods of time.

- Decreasing holding costs - The less expensive a product is to keep in inventory, the longer it can be stored for a potential sale.

- Reducing search costs - The more readily and easily potential buyers can locate depreciated items, the more likely they will be to attempt to acquire them.

Exceptions

Although the above model is an improvement upon price skimming, it features a hidden assumption: that a vendor only has a single opportunity to profit from a given offering.

Many vendors can employ more complex business models to increase their profits.

- Given a sufficiently low rate of depreciation, vendors may find it profitable to lease their items before selling them. This would allow vendors the opportunity to profit from multiple levels of skimming for each item in their inventories.

- As the useful lifespan of the good increases, vendors may prefer to sell their products at relatively high discounts, in order to capture profit from maintenance contracts. Car dealerships, for instance, earn more from repair work than they do from the sale of new vehicles.

- A subset of vendors may find it advantageous to increase the rate at which their offerings depreciate. Planned obsolescence is often used under the theory that consumers will be likely to associate the products at the levels of value experienced early in their life cycle rather than at the levels typically experienced after the offering has undergone severe degradation.

Conclusion

Depreciation is often ignored by anyone outside of the tax accounting field. This is a terrible mistake. In order to maximize their profits, vendors should take an active role in managing the depreciation of their products as they price and market their offerings. Ignoring this will necessarily lead to a reduction in pricing power and a weakening of strategic position.

Questions come from readers like you. If you'd like your questions answered, send them my way.

Pricing in the News

- SUPREME COURT SIDES WITH PATIENTS, PHYSICANS, & PHARMACISTS

- Robinhood Financial to pay $65 million to settle SEC charges of misleading customers

- Can't get a PlayStation 5? Meet the Grinch bots snapping up the holidays' hottest gift.

- What Are You Paying For in a $300 Chess Set? Mostly the Knights

- When Money Is Free, Lenders Start Charging for Everything Else

- It may be legal, but high prices and inconvenience may drive black-market marijuana for years

- Grubhub gig workers react angrily to change in tipping policy

- HHS: Distilleries won't have to pay FDA fees of more than $14K for making hand sanitizers amid pandemic

From the Blog Archives

- Profit Maximization with Software Engineering Certifications - Are people who rely on certifications truly certifiable?

Notable Pricing Quote

"No man's credit is as good as his money." -- John Dewey

Shameless Commercial Plug

Have you seen this video about how seemingly insignificant changes to systems can lead to massive changes in state?

The same is true for pricing. Tiny modifications to one's pricing can completely transform one's bottom line.

If you're looking for some ideas to improve your pricing, why not pick up a copy of Strategic Pricing: The Novel?